Yachting Magazine – Going Wild

Southeast Alaska: America’s last great Coastal Wilderness

Story and Photography by Peter Frederiksen as seen in Yachting Magazine – March

As I paddled toward a small iceberg near an unnamed cove on Holkham Bay at the mouth of the Tracy Arm in southeast Alaska, I almost jumped out of my kayak. The gently rocking, placid looking blue ice the size of a trailer load of Land Rovers was creating a suction around its periphery pulling my plastic boat toward it. Saltwater slapping against the iceberg made a clackity racket. But over the din as I dipped my paddle in the cold green water to move away I pondered how Tlingit Indian hunters survived in their tiny craft with a winter’s worth of freshly killed animal sustenance strapped to the hood. Such contrasts best describe Alaska and the six days I spent aboard Alaska Song last August.

As I paddled toward a small iceberg near an unnamed cove on Holkham Bay at the mouth of the Tracy Arm in southeast Alaska, I almost jumped out of my kayak. The gently rocking, placid looking blue ice the size of a trailer load of Land Rovers was creating a suction around its periphery pulling my plastic boat toward it. Saltwater slapping against the iceberg made a clackity racket. But over the din as I dipped my paddle in the cold green water to move away I pondered how Tlingit Indian hunters survived in their tiny craft with a winter’s worth of freshly killed animal sustenance strapped to the hood. Such contrasts best describe Alaska and the six days I spent aboard Alaska Song last August.

Capt. Geoff Wilson and his wife, Debbie Bennett, have been chartering in southeast Alaska for 10 years and their experience, shows in the day-to-day itinerary. Capt. Geoff’s niece, Jessica Adkins, nephew, Reno Jacobson and Debbie’s perky westie terrier, Damien, round out the crew. Operating between Juneau and Sitka in the Tongass National Forest, the 96′ Alaskan Song makes six-day trips between the ports anchoring out each evening in quiet, desolate coves.

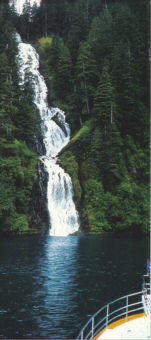

Leaving the state capitol at noon under sunny skies, we cruised down Gastineau Channel into Stephens Passage, a gorgeous waterway lined with Sitka spruce, western hemlocks, pine, alders and Alaska cypress trees heading toward Tracy Arm, a fjord 45 miles south of Juneau. After spending the first night anchored in that unnamed cove on the western side of Holkham Bay, we would negotiate the 25 miles of icy waters up to Sawyer Glacier in the morning. Tracy Arm twists and turns between Yosemite-like cliffs and waterfalls, but it didn’t prepare me for the size of the glacier framed by mountain peeks that soar some 7,000 feet.

The Glacier’s presence can be seen and felt long before it comes into view. Tracy Arm is littered with small to medium icebergs that must be respected considering the bulk of the ice is beneath the surface. Even at the modest 9 knots, Capt. Geoff had to jockey the wheel to keep the prow of Alaskan Song from crunching into the chunks of ice drifting toward open water. Watching the surface water temperature gauge at the helm plunge from 50 to 37.9 degrees was another clue the deeper we invaded the fjord. As for the air temperature, when the summer breeze blowing past a berg reached the flying bridge, it felt like march in Manhattan.

A glacier is a river of moving ice and while it’s tempting to get close to the base for a better look at lounging harbor seals, there’s the ever present danger of calving, when a portion of ice separates from the flow and crashes into the water. Since it’s almost 100 fathoms deep at the end of the fjord, calving can create 25′ waves here. You don’t take chances in Alaska. That’s why I couldn’t resist a ride later that day with Don Kyte, a retired 747 pilot in his 1947 Republic RC-3 Seabee to see the Dawes glacier in nearby Endicott Arm. Since the plane’s “whale belly” allows it to take off and land in water, Don taxied right up the boat’s swim platform. The view from 3,000′ was breathtaking and Don’s commentary about how the tributary Ford’s Terror was named for the British seamen who came face to face with the area’s 18 knot current on a rising tide had me mesmerized. The sight of two humpback whales in Stephens Passage as we flew south to catch up with Alaskan Song was an added treat. But not as much as Debbie’s oven-roasted Cornish hens and lip-smacking peach cobbler dessert that evening in a tranquil anchorage between two small wooded island known as The Brothers.

look at lounging harbor seals, there’s the ever present danger of calving, when a portion of ice separates from the flow and crashes into the water. Since it’s almost 100 fathoms deep at the end of the fjord, calving can create 25′ waves here. You don’t take chances in Alaska. That’s why I couldn’t resist a ride later that day with Don Kyte, a retired 747 pilot in his 1947 Republic RC-3 Seabee to see the Dawes glacier in nearby Endicott Arm. Since the plane’s “whale belly” allows it to take off and land in water, Don taxied right up the boat’s swim platform. The view from 3,000′ was breathtaking and Don’s commentary about how the tributary Ford’s Terror was named for the British seamen who came face to face with the area’s 18 knot current on a rising tide had me mesmerized. The sight of two humpback whales in Stephens Passage as we flew south to catch up with Alaskan Song was an added treat. But not as much as Debbie’s oven-roasted Cornish hens and lip-smacking peach cobbler dessert that evening in a tranquil anchorage between two small wooded island known as The Brothers.

After a morning hike on West Brother, we moved south toward Kupreanof Island to soak herring baits for halibut and salmon. Capt. Geoff put us into fish on every drift. We kept a few for dinner and returned most for seed.

In Alaska where the fishing is almost always better than you will find anywhere else, it’s imperative to practice conservation. I was especially happy turning a 120-LB. halibut loose, since the larger ones are breeding females. But I was less relieved seeing the blatant clear cutting of the island’s north shore forest.

Later in the day on the west side of Kupreanof Island between Cape Bendel and Pt. Macartney, Capt. Geoff found a pod of humpback whales that stayed busy feeding for hours. I’ve seen whales before, but never experienced watching a pod work together like this. According to Capt. Geoff and Debbie, the lead whale, a female, communicates with the others directing them as they maneuver beneath the forage. The whales blow bubbles and as the turbulence called bubble nets floats upward it corrals herring and krill into a ball. With open mouths the whales smash into the herd of bait as they breach the surface. To see and hear 30-ton animals clearing the water is a drama that never grows old.

When the whales moved off, we headed toward Pt. Pybus 16 miles to the north to check out a killer whale report. According to Capt. Geoff there are two known resident pods of killer whales in Alaska which have been tagged AF and AG by marine scientists. Supposedly the resident pods aren’t as aggressive to other seagoing mammals like seals and sea lions. Maybe it’s because the other mammals are smart enough to stay out of these neighborhoods. All I can report is that when you see a six’ dorsal fin of a 26′ adult male that weighs 8 tons slide underneath the pulpit, you know this is no scene from a “Free Willy” flick. The law states that boats must keep 100 yards away from marine mammals but all you can do when they swim toward you is sit tight, hold your breath and watch. We caught the tail end of a good show before Capt. Geoff aimed Alaskan Song into Cannery Cove in Pybus Bay on the southeast coast of Admiralty Island.

When the whales moved off, we headed toward Pt. Pybus 16 miles to the north to check out a killer whale report. According to Capt. Geoff there are two known resident pods of killer whales in Alaska which have been tagged AF and AG by marine scientists. Supposedly the resident pods aren’t as aggressive to other seagoing mammals like seals and sea lions. Maybe it’s because the other mammals are smart enough to stay out of these neighborhoods. All I can report is that when you see a six’ dorsal fin of a 26′ adult male that weighs 8 tons slide underneath the pulpit, you know this is no scene from a “Free Willy” flick. The law states that boats must keep 100 yards away from marine mammals but all you can do when they swim toward you is sit tight, hold your breath and watch. We caught the tail end of a good show before Capt. Geoff aimed Alaskan Song into Cannery Cove in Pybus Bay on the southeast coast of Admiralty Island.

Admiralty has the largest concentration of grizzly brown bears in the world and two were working the shoreline when I went on deck the next morning. At least that is all I saw. But it was the hungry bugs that made a bigger impression on me when Debbie took us ashore to dig clams at low tide. It didn’t take long to fill a bucket and I looked forward to a meal of the steamed bivalves while swatting flies with muddy hands. Just as important, I never stopped looking out for bears while digging in the mud. You truly feel like a stranger in a strange land in this beautiful part of the world.

We tried trolling for salmon the next morning but with the main king run over, we never had a strike. But later in the afternoon when we entered Red Bluff Bay on Baranof Island we cast to the pink salmon stacked up like cans on a shelf, while watching commercial boats fill their nets. Bald eagles, numerous as black Chevy trucks in the parking lot of a Nascar race, watched everything.

Some 15 miles north of Red Bluff Bay at Warm Spring Bay is the settlement of Baranof established around 1900. The home of a hot spring fed by fissures in the rock wedged between a crystal clear lake and magnificent waterfall, Baranof offered a chance to stretch our legs on land. The hot spring and steep trail to it are maintained by the forest service and sundries are available at the general store. A few of the homes there sprouted satellite dishes from their roofs, somewhat incongruous in this natural setting.

Back aboard Alaskan Song we steamed 10 miles north in Chatham Strait to the fish hatchery at Hidden Falls in Kasnyku Bay which produces 75 million chum, 1.1 million king and 1.5 million coho salmon each year. Built in 1978 and operated by the state until 1988, the hatchery is now privately run by and for commercial and sportfishing interests. There’s some conflict about hatchery stock mingling with native fish but I left wondering how many of the manually fertilized salmon eggs would hatch, how many fry would survive, who would catch the ones that did and which ones would make it back to the river to spawn years later? That night under a soft summer rain, we shared an anchorage in Sitkoh Bay on Chichagof Island with the Alaska Whale Foundation’s research vessel, Evolution. On the south shore of Sitkoh Bay is the settlement of Chatham and the remains of an inactive salmon cannery. Where there once was fishermen and boats, there are now eagles sitting around perhaps waiting for another run. Like hopeful fishermen, maybe the eagles feel tomorrow will be the day.

The following morning after releasing a lost Dungeness crab that wandered into our pot during the night, we pulled anchor. While Evolution headed east into Chatham Strait searching for whales, Capt. Geoff let us fish for an hour off Morris Reef. There were a lot more salmon at the Hidden Falls hatchery.

But as we entered Peril Strait on the backside of our adventure, we were suddenly surrounded by a very lively pod of orcas that put on a show for miles. orcas feed differently from humpbacks and move more quickly. But it was fascinating watching these toothed whales function as a family unit. The mothers kept the babies close by but every now and again a young orca would break the surface, gulp some air and then wiggle its dorsal fin as it dove. I wasn’t sure if the little orcas were waving at me or Damien who barked each time the whales cleared their blow hole.

Our last anchorage was in secluded Katlian Bay, a surprise being so close to Sitka. But then Alaska is full of surprises for anyone who appreciates the beauty and contrasts of the final frontier.

I only wish I could have made the reverse run from Sitka to Juneau. Somehow I know it would be all different like everyday in Alaska.